Despite all the advances in science and technology we still have a lot to learn from the past writes David Chalfen

Thank the running heavens for the blessings of sports science and technology to enable the best distance runners to truly max out their great ability. Otherwise, we’d be stuck back in the dark ploddy days of the 1980s when the best that a British male – or pretty much anyone else, from anywhere at sea level – could muster over 5000m metres was 13.00.41 (1982 – imagine that, 13 flat for 5000 being seen as a great benchmark!), 27.23 at 10,000 (1988) or a clanky 2.07.13 marathon (1985).

Hey; hold on a minute; aren’t those times pretty tasty, around 35 years later? Where does this fit with all the reams of academic papers, books and now digital information on what we usually call ‘cutting edge’ or ‘state of the art’ advances?

Cast your eye down the IAAF All Time lists, and look away from the many altitude reared athletes who have sensibly and lucratively turned their tremendous natural and environmental advantages to long distance running. You’ll notice that the numbers of sea level runners, from the whole planet, over 4 decades, who have surpassed these landmark performances (Dave Moorcroft, Eamonn Martin, and Steve Jones, for the uninitiated) is truly tiny, as are the margins by which they have improved what were all pre-Mo UK records.

Strip out those runners who in all likelihood had the benefits of some clandestine ‘Mediterranean red wine’ and the pool of progression is even tinier. (If you wish to play Aerobic Sherlock, EPO tests came into play from 2000/01)

So barely 1% of progress, by my maths. Which is interesting given how many different one per centers we must have been offered over the years. This brings to mind one of the many gems in Alex Hutchinson’s tremendous book Endure, where he quotes leading Canadian coach Dr Trent Stellingwerff’s reference to “ 1% + 1% + 1% +1% = 1%”.

That is, put facetiously by yours truly, with all these one per centers popping up yearly, we should surely be down to about 25 minutes for 10,000m or 1 hour 55 for the marathon. And that’s for the U20 women…. .

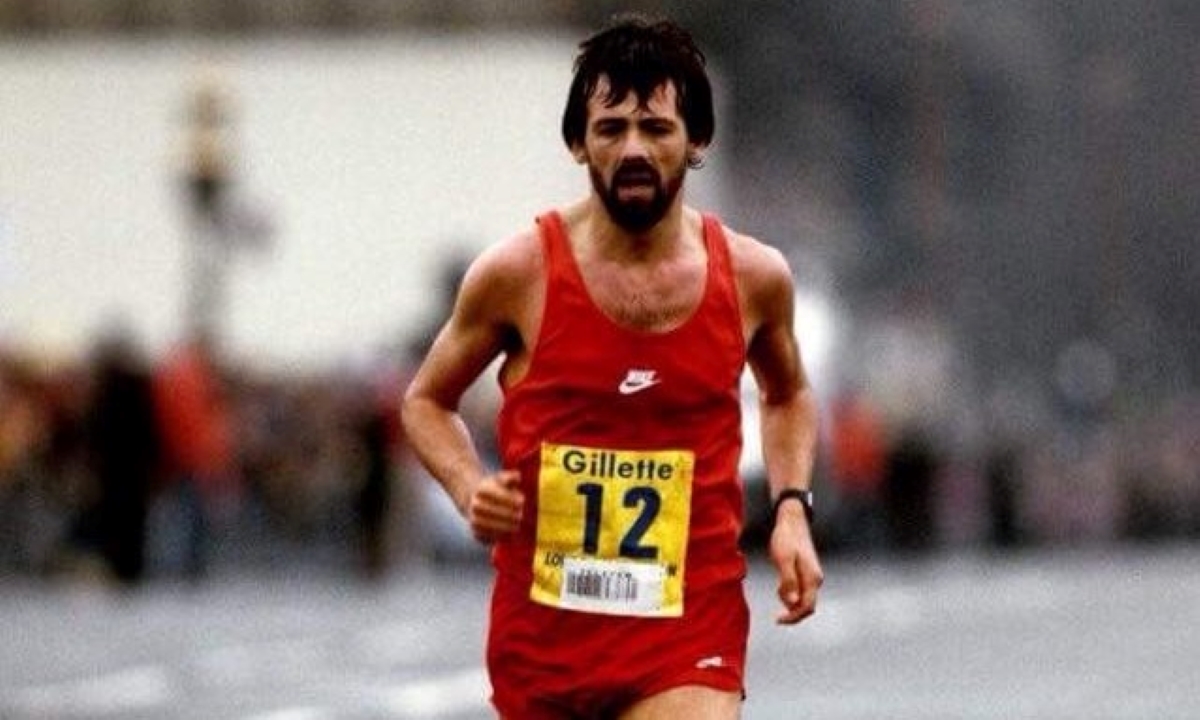

Mike Gratton victorious in London in ’83 – he spoke Shaun on a recent Let’s Get Running Podcast

Eamonn Martin and Jon Brown, the two UK 10,000m record holders before Mo Farah, have both gone on record stating bemusement and disappointment in the GB context but the relative stasis applies to 99% of the world’s nations – the world that isn’t the Rift Valley.

Makes you wonder – are there really 200-plus nations where youngsters have been subjected to too much TV or screen time, too many fry ups and takeaways, or local councils selling off playing fields for a mock Tudor housing estate?

Put it another way; set aside the sports medicine advances which thankfully keep runners’ careers going for longer than was often the case 35 years ago; and the more meticulous use of altitude training, and look just at what running the very best current runners do. Go through the detail of volume/intensity/pace/recovery/periodization. Then go and look at what their counterparts did more than a generation ago, and then flag up what you see as the relevant advances.

Even if we treat the marathon as a special case for training advances over the decades (in 1985 sub 2.10 was still a benchmark of world class in a way that it really isn’t anymore), the Steve Jones legend (interestingly achieved with a half way split of 61.50) has moved on barely 1% by barely a dozen athletes.

What has changed significantly from the 1980s is that the sport (coaches, managers, sponsors primarily) has become much more adept at identifying, nurturing and retaining the best endurance running talent in the species and incentivising and rewarding performance.

Any coaching points? Perhaps, twofold. Firstly, ‘wood for the trees’ – don’t get blindsided by tiny marginal aspects before fully embracing the fundamentals. Well you can, but if you are training 25 mpw and angsting over the concentration of your beetroot juice maybe step back for a moment.

Secondly, just because it happened 35 years ago and in many ways the world has moved on hugely, that doesn’t mean it may not still be best practice, at least for the specific individual concerned. So, Dave Moorcroft’s West Midlands canal networks or Jacob Ingebritsen’s Sandnes small town idyll; Steve Jones’s RAF St Athan flexi day job or Sondre Moen splitting his peak training between Sestriere and Kenya?

David Chalfen supports beetroot juice, designer mattresses and Nike Next%; and also just heading out the effing door with your kit on, frequently.